The Lovely Weather Donegal Residencies was a Leonardo/Olats art-and-climate project that took place in Donegal, Ireland, in 2009-10. As one of 5 commissioned artists, my artist-residency project - titled WeatherProof - was undertaken in the River Finn Valley. Recently I have written responses to researcher questions about the residencies. They are presented below.

Q: The level of community engagement and how this was organised

My understanding is that there was a high degree of community

engagement extending through all stages of the project. I wasn’t involved with the inception, but I know that elected

representatives were involved with the initial stages and selection of artists...

For the five artist residencies, very different methods of engagement occurred. In my project WeatherProof, located largely within the River Finn Valley, I linked up with the local postman, Michael Gallagher, who was happy to participate and to facilitate wider interactions with the local community. In this way, I made contact with the local school (Dooish National School) and, in particular, developed an ongoing conversation with the former head teacher, who was active in campaigns relating to local ecology and land/water management. In turn there were further introductions, and gradually there developed a loose network of key participants. Most of these were involved with my eventual installation work at The Regional Cultural Centre, and a large school group was able to visit the exhibition and be introduced to the work they helped create.

For the other four artist residencies, there were diverse approaches to engagement. In a project by Seema Goel, a local knitting group was I believe the main community involvement point, and in the project by Soft Day, there was a process leading to the creation of a performative event with local musicians and a majorette group (filmed for later exhibition).

In essence, the methods were varied, but overall the extended length of the projects (a year or more) enabled a slow evolution of relationships - despite the fact that some of the artists were based overseas. An important facet of the project was the participation of the scientific community. Each artist or artist-group had extended dialogues with specific climate-science researchers - in my case with paleo-ecologists at Queens University, Belfast.

Q: The public impact of the residency and local legacy

The main public impact was via the end-of-project exhibition in Letterkenny, hosted by the Regional Cultural Centre, which was also the base of operations for the whole project. This enabled the works to be shown to a broad audience.

Linked to this was a 1-day conference on art and climate change, including joint presentations by the artists and their scientific and community contacts.

A publication (booklet) by Donegal County Council and a website helped extend the reach, as did coverage on national and regional TV.

For a more specialised audience, there were short articles by each of the artists in an issue of the Leonardo Journal.

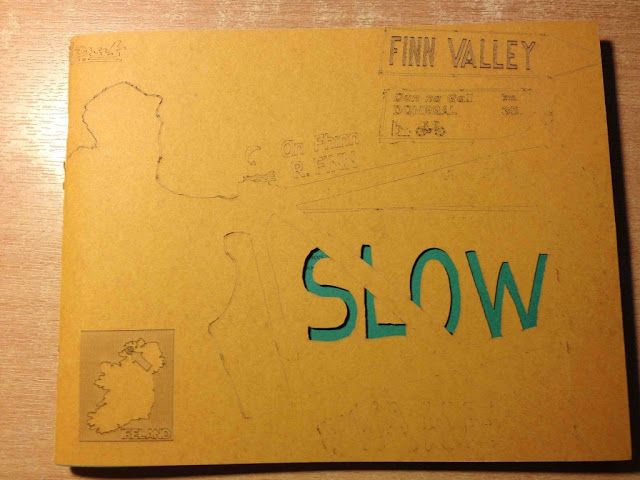

Furthermore - for my element - I produced an artist book which replicated an online blog that I had maintained throughout the project (no longer available online).

[book content available here: https://www.academia.edu/40636893/Weatherproof_one_half_of_an_artist_research_book ]

Q: Practical support from the commissioners

This project was exceptionally well supported from the start. The co-curation with the international Leonardo project was important in giving the whole process a solid foundation, and in building support locally.

In terms of practical assistance, the resources dedicated to artist support were extremely robust and varied. This extended from assistance with concept development, artist group dialogues, accommodation & logistics, community participation support and much else. The dedicated team at the Regional Cultural Centre and the County Council Arts Office was always available for assistance and discussion.

This was also especially evident in the stage of creation of the exhibition, where a team of technicians and support staff were actively engaged with assembling (and disassembling) the complex and very ambitious works.

Q: In your view what is the role of these types of residencies in addressing the climate crisis

I feel this form of extended embedded residency plays a very important role. In the aftermath of the Lovely Weather project, I have sought to conduct similar extended (1-year plus) residencies dealing with ecology, climate change and landscape change.

Creative processes and works can have a impact in reaching people in ways that are beyond or differ from the more standard news/information/science communications. The concept of a place-embedded or community-embedded ‘outsider’ artist can also spark or prompt fresh contemplation or understanding of complex eco-social issues such as climate change and biodiversity collapse.

By necessity, different strands of knowledge and understanding (factual, emotional, imaginative, empathic etc.) need to be intertwined and synergistically interact in order to address - or survive - the multiple complex challenges that face our societies and communities. Creative practice - being focussed on sensitivity, tuning-in and holistic appreciation - is a good vehicle for such expanded awareness (which I have tended to describe as ‘geopoetic’). In part, this can be about a form of re-building or re-making a sensitive connection to the dynamics of a place, both human and non-human. But even more so, it can be about citizen empowerment, through assisting to create, or imagine, new futures and new directions. I feel this is the real value of these type of projects; to help envisage better worlds and deeper ecological connection.

Q: What is the expectation of artists in this line of work and is it realistic?

In lieu of ‘expectation’, I would maybe use the terms ‘ambition’ and ‘aspiration’. These orbit around the questions of making meaningful connections and creative research; making satisfying work to share; and feeling that there are on-going ripples of ‘activity’ in the wake of a creative project. These ripples happen both locally and within his/her artistic practice. The notion of a transferable experience and learning forms part of this.

For me, the key aspects that makes such aims ‘realistic’ are a) duration and b) support. There are both essential in gaining traction with a situation, a place and a community. In terms of ‘duration’ the minimum time period for such projects should ideally be 1 year. In my experience, the ideal is closer to 3 years. This allows for slow emergence of themes and relationships. It also facilitates experimentation - and failures as well as successes.

e.g my initial aspirations to assemble and maintain a small volunteer observation team (recording diary entries) and to also create a geo-caching trail did not come to fruition, and the involvements took on a different form.

Artist residencies do not need to equate to continuous presence in a place (and Lovely Weather residency times were very intermittent), but do need to have the leeway to allow organic emergence of growth and flourishing. In a way the term ‘residency’ is misleading and could perhaps be replaced with alternative terminology.

Q: Ten years since the project, what are the key learnings, recommendations and points of consideration for commissioners planning public art projects relating to the climate crisis?

In essence, related to the points I’ve made already, I feel some key suggestions could be:

- Enable multi-year place/community-embedded projects that focus more on process rather than specific product.

- Assign sufficient support in the form of fee, expenses, logistics and curatorial support

- Maintain trust in the creative approach and methods, bearing in mind that genuine and meaningful work emerges from trial-and-error and iterative reflection.

- Assist with community contacts, but be flexible and non-prescriptive as the journeys of connection and engagement are meandering and unpredictable.

- Where possible (depending on funding source), try to avoid a ‘numbers game’ in terms of engagement and participation targets. A sophisticated approach should be able to understand that deeper inroads into understanding of place/community/topic can often be achieved via individuals or small groups, as opposed to larger groups. Artist walks, talks and conversations can help build understanding and support in the community.

- There are paradigm shifts underway in relation to public art. Public understanding pf process-based and ephemeral (non-permanent) work needs to be fostered over time.

Q: Can public art policy influence environmental policy?

I feel these should ideally be linked and to mutually co-influence.

Public art initiatives have the ability to be indirect sounding boards for policy aspirations, and - in turn - public art strategies should ideally be founded on both social and ecological concerns and aims.

In an expanded view, there is of course a strong argument to be made for fuller integration (of public art and creative projects) in other plans and strategies, such as heritage (natural and cultural); economic and development policies, including tourism.

Finally, public art of this form can be stimulating and useful. However it is important that the creative processes not be instrumentalised and treated solely as tools for achievement of broader engagement/consultation programmes. There probably needs to be more of a culture shift to fully embrace provocative artistic practice as core to social and ecological functioning.

LINKS and Info

Donegal County Council content

http://donegalpublicart.ie/dpa_lovelyweather.html

Text from the above Donegal County Council site

(initial proposal)

Weather-Proof

‘Slowness’ is the key to Antony Lyons’ project. In the Ballybofey / Stranolar area, a look-out point, which is also an existing field-gate, will be selected. The site will be close to a location where scientific weather measurements (rainfall, humidity, temperature, pressure, wind speed, wind direction) are already being taken. This will become the site for year-long observation (by the artist and some observers). At the gate / look-out site, the artist’s recordings will be highly personal weather-words/ weather-diaries recorded on paper and digitally with photos and sounds. The programmed visits by the artist will be supplemented by daily/weekly visits by members of a small volunteer observation team. Furthermore, there is the potential to extend the observer participation into the idea of a geo-caching trail, with weather-proof boxes located at points in the landscape.

My content for the Leonardo Journal:

http://www.antonylyons.net/antony/enquiry_files/WeatherProof_1.pdf

Content from related artist-book:

https://www.academia.edu/40636893/Weatherproof_one_half_of_an_artist-research_book

(includes an essay by Annick Bureaud, co-curator of the project on behalf of Leonardo)

A project description, with further links:

https://antonylyons.carbonmade.com/projects/4611882